CD booklet – Programme Notes for

The Captive Nightingale/The Shepherd and the Mermaid

Written by Derek Watson

Nineteenth century art song was firmly harnessed to the instrument found in every genteel home – the piano. Other available players were eagerly welcomed to the salon and editions were published with ad libitum or obbligato parts for violin, flute, horn, cello, harmonium, and the instrument outstandingly raised in status by Mozart and Weber, and well suited in range and tone colour – the clarinet. The winning combination of voice, clarinet and piano delighted intimate gatherings and inspired many lovely works.

Musical history owes much to clarinettists whose talents stimulated a series of compositions: Anton Stadler with Mozart, Heinrich Bärmann with Weber, Richard Mühlfeld with Brahms, and Johann Simon Hermstedt in the case of both Spohr and Andreas Späth. London-born Henry Lazarus (1815-95), probably the finest English clarinettist of his day and an influential teacher, did much to popularise music with obbligato clarinet including the song by Kreutzer chosen here. Clarinets, like pianos, underwent significant technical improvements during the Romantic era. Domestic circumstances would often prompt the substitution of one ‘obbligato’ instrument for another of similar range: the clarinet taking a violin part for example.

That much of the music on this disc was long forgotten is symptomatic of the neglect of this repertory. A ‘Lieder recital’ gradually established itself in the concert hall rather than the household, predominantly with voice and piano alone, and the twentieth century turned a largely deaf ear to the perceived sentimentality or Biedermeier qualities of ‘salon music’. Discovering items long overlooked can bring many rewards. One item in this recital, the iconic song for this combination, Schubert’s Shepherd on the Rock, has always been admired and performed, and exerted its influence in subject matter and style on others heard here.

Most of our featured composers held court appointments. Schubert again is the notable exception as he had little affinity with that world. The early nineteenth century Kapellmeister was both court composer and orchestral conductor – the latter still a novel role. Kalliwoda, Kreutzer, Lachner, Lindpaintner, Proch and Späth all had busy careers as conductors both of concerts and in the opera house, and all of them composed operas too.

These songs frequently breathe and exhale pure mountain air. Countless contemporary verses were penned in praise of the Alps: love or longing for an Alpine homeland, its mountains, streams, woods and valleys, and its denizens – shepherds, milkmaids, the flocks and herds, the tinkling of their bells. This simple, sunny celebration of nature is occasionally clouded by doubt (the little hesitation in the penultimate line of the first Kalliwoda song), the urge to wander (‘to wander is the Romantic condition’, as Alfred Brendel writes), lovelorn loneliness, or the pain of homesickness. These emotions abound in the texts set here. Another commonplace of these Romantic lyrics is absence: yearning for a lost home or a distant beloved, or for both. German composers delighted too in mingling the natural and supernatural worlds both in opera and the Lied: spirits of mountain, of forest, and of the watery deeps, haunt the Romantic landscape.

Swiss melodies of hill and valley, Kuhreihen or Ranz des vaches, ideally suited to improved clarinet technique and timbre, became a favourite in opera houses and the home. From the arpeggios that herald both Der Sennin Heimweh and Der Hirt auf dem Felsen to the joyous piping-in of the spring in the last section of the Schubert song we hear gentle echoes and sparklingly transfigured forms of yodelling.

Johann Baptist Wenzel Kalliwoda [Jan Křtitel Václav Kalivoda] (1801-66) studied violin and composition at the Conservatory of his native Prague. He spent most of his career conducting Prince von Fürstenberg’s orchestra at Donaueschingen, married the opera singer Teresa Brunetti (1803-92), and their son Wilhelm served as Kapellmeister at Karlsruhe. Kalliwoda’s output was large (Der Sennin Heimweh of 1862 is his opus 236), including 2 operas, orchestral, chamber and piano works; his songs were widely admired. Both Heimatlied (Song of Home) and the later song are characteristically tender reflections on the theme of no place like home. Whenever the music strays into the minor mode, that mood is soon dispelled with a return to the major and affirmation of where the heart truly lies, comfortingly consoled by the clarinet’s gentle yodelling. (The homesick girl of the second song is a Sennin: contraction of a word for an Alpine dairymaid, Sennerin.)

Johann Baptist Wenzel Kalliwoda [Jan Křtitel Václav Kalivoda] (1801-66) studied violin and composition at the Conservatory of his native Prague. He spent most of his career conducting Prince von Fürstenberg’s orchestra at Donaueschingen, married the opera singer Teresa Brunetti (1803-92), and their son Wilhelm served as Kapellmeister at Karlsruhe. Kalliwoda’s output was large (Der Sennin Heimweh of 1862 is his opus 236), including 2 operas, orchestral, chamber and piano works; his songs were widely admired. Both Heimatlied (Song of Home) and the later song are characteristically tender reflections on the theme of no place like home. Whenever the music strays into the minor mode, that mood is soon dispelled with a return to the major and affirmation of where the heart truly lies, comfortingly consoled by the clarinet’s gentle yodelling. (The homesick girl of the second song is a Sennin: contraction of a word for an Alpine dairymaid, Sennerin.)

Conradin Kreutzer (1780-1849) was Kapellmeister first at Stuttgart and Donaueschingen (where he was succeeded by Kalliwoda), subsequently director from time to time of the Kärntnerthor and Josefstadt theatres in Vienna, and in Paris, Cologne and Mainz. Of his circa 40 operas Das Nachtlager in Granada (1834) had lasting renown; the others embrace the gamut of Romantic themes such as the Tyrolean Die Alpenhütte (1815) and the water-spirit Melusine (1833). On listening to the effective clarinet part here, it will come as no surprise that Kreutzer was a noted clarinettist; he composed much for his instrument. In Stuttgart he formed a lasting friendship with Ludwig Uhland whose verses he often set. Das Mühlrad (perhaps an apposite subject as Kreutzers’s father was a Swabian miller!) has been attributed to Uhland, but is adapted from a poem by Eichendorff usually known as Das zerbrochene Ringlein. The images of an endlessly turning millwheel (broken chord piano figures), a lover’s ring forever broken, the poet’s wish to escape life and so silence both the wheel and his grief forever are starkly but simply conveyed with subtle touches that would not disgrace the composer of Die schöne Müllerin.

Conradin Kreutzer (1780-1849) was Kapellmeister first at Stuttgart and Donaueschingen (where he was succeeded by Kalliwoda), subsequently director from time to time of the Kärntnerthor and Josefstadt theatres in Vienna, and in Paris, Cologne and Mainz. Of his circa 40 operas Das Nachtlager in Granada (1834) had lasting renown; the others embrace the gamut of Romantic themes such as the Tyrolean Die Alpenhütte (1815) and the water-spirit Melusine (1833). On listening to the effective clarinet part here, it will come as no surprise that Kreutzer was a noted clarinettist; he composed much for his instrument. In Stuttgart he formed a lasting friendship with Ludwig Uhland whose verses he often set. Das Mühlrad (perhaps an apposite subject as Kreutzers’s father was a Swabian miller!) has been attributed to Uhland, but is adapted from a poem by Eichendorff usually known as Das zerbrochene Ringlein. The images of an endlessly turning millwheel (broken chord piano figures), a lover’s ring forever broken, the poet’s wish to escape life and so silence both the wheel and his grief forever are starkly but simply conveyed with subtle touches that would not disgrace the composer of Die schöne Müllerin.

Heinrich Proch (1809-78) was a well-known Viennese conductor and singing teacher; pupils included Materna, Dustmann and Tietjens, and his daughter Louise was a professional singer. He composed an opera, operettas and over 200 songs. Both examples here again express longing for home. Schweitzers Heimweh (Op.38, 1847) gives patriotic voice to a Swiss exile in an uncongenial land. In Die gefangene Nachtigall (Op.11, 1842) the misery of a caged nightingale pining for forest freedom is characterised by the piteously faltering repeated notes that begin the clarinet’s introduction.

Heinrich Proch (1809-78) was a well-known Viennese conductor and singing teacher; pupils included Materna, Dustmann and Tietjens, and his daughter Louise was a professional singer. He composed an opera, operettas and over 200 songs. Both examples here again express longing for home. Schweitzers Heimweh (Op.38, 1847) gives patriotic voice to a Swiss exile in an uncongenial land. In Die gefangene Nachtigall (Op.11, 1842) the misery of a caged nightingale pining for forest freedom is characterised by the piteously faltering repeated notes that begin the clarinet’s introduction.

Andreas Späth (1792-1876) was born at Rossach near Coburg and received his musical training at the Hofkapelle of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, excelling in composition, keyboard and clarinet. He took an appointment as organist in Switzerland in 1822 and from 1833 was music director in Neuchatel, returning to Coburg as Kapellmeister and court organist in 1838. He composed 5 operas and wrote a significant corpus of clarinet music. This song of 1839, Op. 167 No.7, was published as an appendix to his Sechs Schweizer Lieder.

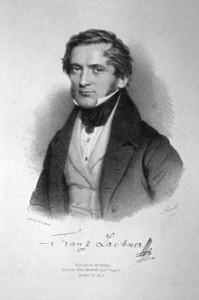

Schubert’s friend Franz Lachner (1803-90) hailed from a talented Bavarian family of musicians, completed his studies in Vienna, then began his career as deputy Kapellmeister at the city’s Kärntnerthor Theater, soon rising to principal Kapellmeister (alongside Conradin Kreutzer). After two years in Mannheim he became Hofkapellmeister at the Munich court (1836) until the advent of Wagner there in the mid-1860s. (Ironically Lachner’s conducting paved the way for Wagner by improving orchestral standards and introducing Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.) Greatly respected in his day for his operas, choral works, 8 symphonies and other orchestral pieces, concertos, chamber music, many songs, organ and piano music, the products of this huge industry lay largely neglected for a century after his death. Lately there has been a notable revival of interest in his oeuvre. Influenced much by Schubert, Lachner also had a fondness for the ‘trio’ combination of voice, piano, plus horn or cello or clarinet. The songs on this disc are from his Frauenliebe und –Leben Op.82 (published 1847), settings of the cycle of poems by Adalbert von Chamisso which Robert Schumann and Carl Loewe also used.

Schubert’s friend Franz Lachner (1803-90) hailed from a talented Bavarian family of musicians, completed his studies in Vienna, then began his career as deputy Kapellmeister at the city’s Kärntnerthor Theater, soon rising to principal Kapellmeister (alongside Conradin Kreutzer). After two years in Mannheim he became Hofkapellmeister at the Munich court (1836) until the advent of Wagner there in the mid-1860s. (Ironically Lachner’s conducting paved the way for Wagner by improving orchestral standards and introducing Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.) Greatly respected in his day for his operas, choral works, 8 symphonies and other orchestral pieces, concertos, chamber music, many songs, organ and piano music, the products of this huge industry lay largely neglected for a century after his death. Lately there has been a notable revival of interest in his oeuvre. Influenced much by Schubert, Lachner also had a fondness for the ‘trio’ combination of voice, piano, plus horn or cello or clarinet. The songs on this disc are from his Frauenliebe und –Leben Op.82 (published 1847), settings of the cycle of poems by Adalbert von Chamisso which Robert Schumann and Carl Loewe also used.

Die verschworenen (The Conspirators) is a 1-act comic Singspiel completed in the spring of 1823 by Franz Schubert (1797-1828) to a libretto by Ignaz Castelli after Aristophanes. The Viennese censor demanded it be re-titled Der häusliche Krieg (Domestic Warfare). It met with as little success as any of Schubert’s stage works, indeed no theatre would take it up. Ironically after its 1861 Frankfurt premiere it was enthusiastically received all over Europe. The plot, set in medieval Germany, concerns the wives of knights forever absent at war: they conspire to withhold their favours till the men agree to give up fighting and stay at home. The Romance with clarinet obbligato for the young wife Helen is one of the high points of the score.

Die verschworenen (The Conspirators) is a 1-act comic Singspiel completed in the spring of 1823 by Franz Schubert (1797-1828) to a libretto by Ignaz Castelli after Aristophanes. The Viennese censor demanded it be re-titled Der häusliche Krieg (Domestic Warfare). It met with as little success as any of Schubert’s stage works, indeed no theatre would take it up. Ironically after its 1861 Frankfurt premiere it was enthusiastically received all over Europe. The plot, set in medieval Germany, concerns the wives of knights forever absent at war: they conspire to withhold their favours till the men agree to give up fighting and stay at home. The Romance with clarinet obbligato for the young wife Helen is one of the high points of the score.

Der Hirt auf dem Felsen was composed in October 1828, the month before Schubert’s death. Designed as a display piece for a renowned Berlin opera singer Anna Milder-Hauptmann, it stands apart from the great world of his Lieder, not only by including clarinet obbligato, but in its scope, which resembles a miniature cantata. The memorable, graceful opening leads to a truly Schubertian middle section, and the final allegretto bubbles over in radiant anticipation of the spring. Unusually the text is chosen from two authors, Wilhelm Müller (poet of the 2 great Schubert song cycles) and Karl August Varnhagen von Ense (the only verses Schubert ever set of this writer). Müller’s lines for the first 4 verses come from his Der Berghirt (The Mountain Shepherd); Varnhagen’s verses 5-6 (beginning In tiefer Gram; long misattributed to Helmine von Chézy) are from his poem Nächtlicher Schall (Nocturnal Sounds); Schubert freely adapts the final verse from Müller’s Liebesgedanken (Thoughts of Love)

Johann Sobeck (1831-1914), born in Karlsbad, Bohemia, was a clarinettist, trained at Prague Conservatory, who enjoyed a career of fifty years from 1851 as principal clarinet for the Court Orchestra at Hanover. He composed much for his own instrument in a variety of forms – sonatas, concertos, wind quintets, opera fantasias and songs. As with the pieces by clarinettists Kreutzer and Späth, the writing for the wind instrument in Meine Heimat is assured, idiomatic and effectively married to voice and text.

Of the composers represented here most, stylistically, were heirs to Weber. None more so than Peter Joseph von Lindpaintner (1791-1856), born in Koblenz, conductor at Munich’s Isartortheater from 1812, and Kapellmeister at Stuttgart from 1819, where he gained a fine reputation for his conducting and was ennobled as ‘von’ by the King of Württemberg. Of his 20 operas, several treat supernatural subjects in the Schauerromantik vein of Weber’s celebrated Freischütz. Lindpaintner’s Der Bergkönig (1825) and Der Vampyr (produced in the same year – 1828 – as Heinrich Marschner’s opera on the same subject) perfectly illustrate this contemporary fascination with the thrill of the macabre. Just as songs reflected the agendas addressed on a larger scale in opera, so there are famous examples of the Schauer-Lied: Goethe’s Erlkönig (most famously set by the young Schubert) and Heine’s Die Loreley (as vividly set by Liszt). As with Schubert’s boy and Liszt’s fisherman, the music leaves no doubt that Lindpaintner’s shepherd is drawn to his doom by enchantment. In this large-scale virtuoso setting the enticements of the mermaid’s song have a dramatic inevitability: he is lured to the fatal waters.

© Derek Watson 2011